With Apologies to my Lit Crit Buddies by Tom Rich

To complicate the idea from my previous post, allow me to quote from the philosopher Han Solo: “Great, kid, now don’t get cocky.”

Part of the reason, I think, that so many of us downplay our role in the process—aside from undiagnosed depression—is that, in so many cases, stories go wrong explicitly because of things the writer did. We see it all the time in fiction workshops: the students who spend the semester defending their decisions, explaining away unbelievable characters and refusing to acknowledge that their use of “loquacity” is both pompous and, technically, incorrect. Or the writers who are oh-so-clearly writing only to impress the critics, ladling on thick, syrupy symbolism until you can’t critique the damn thing without first authoring a dissertation on it.

Back in high school, when I was working on my totally-awesome-and-in-no-way-derivative fantasy epic, I became obsessed with the present participle: everyone was walking, but nobody walked. When my friend Johannes pointed this out, I replied with the classic “that’s just my style” defense. What he said was “don’t do that,” but you really need the whole picture: he sort of groaned like he was about to do his taxes, rolled his eyes and tilted his head back, pushed the manuscript aside like it was an overcooked steak. The mixture of exhaustion, despair, and contempt in that phrase has dogged me all these years. In a good way.

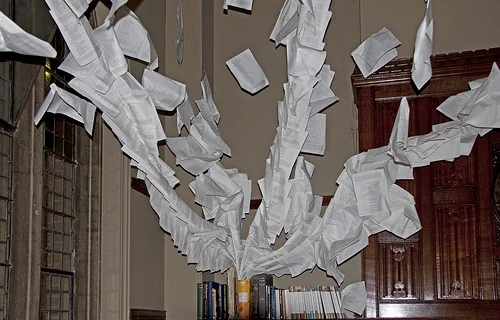

While we’re important, even crucial, to the process, we’re also easily the biggest threat to our own creative success. The writer is responsible for planning, executing, troubleshooting, reviewing, and redoing the entire process. We’re both the oil tanker and the Coast Guard; hell, we’re even the pristine ocean and the picturesque hamlet. We go wrong when we write too much for other writers, when we write too much for readers; when we stick too close or stray too far from our vision; when we revise away the good bits and fail to excise the bad. We fail when we spend too much time on the lofty and when we dwell on the mundane. The whole thing is like one of those 3-D chess games from the original Star Trek, only sometimes, halfway through, it’s revealed that we were actually playing regular checkers all along.

I don’t know of an easy way through the whole mess, and I doubt it’d be worthwhile if there was one, but here’s a trick that you may find useful. Conjure up an imaginary English professor, and give him or her three qualities: first, the finest critical mind of this or any century; second, a rigorous devotion to honesty and accuracy; and third, a seething, rage-fueled antipathy for you and your work. Your imaginary critic should be able to dissect your work, and motivated to do it harshly, but also principled enough to only engage in accurate critiques. Personally, mine is a hip deconstructionist with a black turtleneck who writes lengthy screeds about my writing’s “problematic cultural metanarratives,” but a gray eminence with elbow patches and a deep regard for classical notions of the Western canon would work, too. Go with what feels right, so long as you make it smart, honest, and mean.

Now, read your work as this miserable bastard (it’s alright to imagine him miserable, so long as his critical acumen remains sharp). Imagine what sort of review or critique he would write. Would he call it simplistic? Culturally insensitive? Cliché? Bland? Shitty? You know you’ve succeeded when you’ve reduced your critic to engaging in ad hominem attacks on your character, politics, or drink of choice. The less he’s able to say about the text itself, the better you’ve done. If all he can do is accuse you of writing in a genre, you nailed it. Take a victory lap.

Of course, writing for that guy has its own pitfalls, and I’ve met writers who needed to be less critical of their own work. On the balance, though, I think most of us could stand to be taken to task by a brilliant person who intensely dislikes us. And reducing such a person to spluttering character attacks, if only in your head, is a great satisfaction. Happy writing!

Tom Rich is a writer, itinerant academic, and flannel enthusiast. His work has appeared in the Midwest Literary Magazine. Since graduating from Northern Michigan University in 2011, he has gone professional in filling out applications.