New Year’s Breakfast by Michael Cuglietta

New Year’s Breakfast

I knew something wasn’t right when I pulled into the driveway. The porch light, which my mother always kept on for me, was off. The shades were flickering blue like someone had left the television running, and there was a Toyota parked on the street that I’d never seen before.

I stepped out of my car and walked down to have a closer look. The front bumper was held on with silver Duck tape. A crucifix hung from the rearview mirror. The back bumper had a sticker that said: In case of rapture this car will be unmanned.

My mother had the same bumper sticker on her car, and the crucifix that hung in her window was twice the size as the one in the Toyota.

I unlocked the front door and stepped into the house. The glow from the television was the only light in the room. There were two figures in the center of the couch. I couldn’t make out detail. They were just shadows. The sound of the door, closing behind me, startled them. They separated, fleeing to opposite ends of the couch.

“Mark,” my mother said, “you’re home.”

“Mom?” I turned on the hallway light. She was curled up with a blanket wrapped tightly around her shoulders. There was a pile of clothing on the floor in front of her.

“Turn that light off,” she said, shielding her eyes.

On the other end of the couch I saw a man trying to slip into a pair of khaki pants. He was a stocky man. He had no shoulders and no arms but a big round belly.

“Who’s this guy?” I asked, puffing my chest.

“This is my friend, Ron, from church.”

“This is the guy who got me the Stetson collection?” After my father left, my mother had joined a Christian singles group. A week before Christmas she came home with presents for my sister and me. Instead of Christmas paper they were wrapped in baby blue paper that read It’s a boy.

“Christmas,” my mother reminded us, “is Jesus’ birthday.”

My sister got a set of cheap bath soaps. I got cologne, shaving gel, and a stick of deodorant. The box said Stetson was the scent of the American west. It claimed to give men the confidence that comes from knowing there’s nothing you can’t handle.

“Nice to meet you,” Ron said. He’d found his way into his pants. He stood to shake my hand.

“Please,” I said. “Sit back down.”

“There are cookies in the kitchen,” my mother said. “Ron brought them over for you kids.”

“Where’s Nikki?” I said. “Is Nikki all right?”

“Of course Nikki’s all right,” my mother said. “She’s spending the night at Jennifer’s.”

“I’m going to bed,” I said.

“Happy New Year,” Ron said as I walked past him and into my bedroom.

I slammed the door behind me then kicked off my shoes. Lying on my bed, I listened as my mother said her goodbyes to Ron.

There was a ceiling fan hanging over my bed. Sometimes I liked to watch it go round. If you focus on one blade, follow its rotation, you can slow it down. What once was a blur of speed becomes a single blade, gently making its way around.

My mother knocked on the door. “I just want to make sure you’re okay,” she said.

“Everything’s fine.”

“Do you want to talk?” she asked. Then, after a long silence, she said, “We weren’t doing what you think we were doing. Ron’s a Christian.”

I got up off the bed and locked the door.

“I guess that means you don’t want to talk. I’ll leave you alone.”

I listened as she walked away. I climbed out of my clothes and got under the covers. I wasn’t tired but I figured if I lay there, in the dark like that, eventually I’d fall asleep.

***

I woke up to the smell of bacon. I went to the bathroom for a piss then headed to the coffeemaker. As I filled my mug, my mother said, “It’s the French roast. The one you like.” She was standing over the stove, three pans going, one with strips of bacon, one with scrambled eggs, and another with hash browns.

“And,” she said, opening the oven door, “I got cinnamon rolls.”

I took my coffee into the living room. I went to sit on the couch but, remembering what I had seen the night before, opted for the easy chair instead. I flipped on the morning news and got to work on my coffee.

There was a storm coming in from the Midwest. “If it continues its current path,” the weatherman said to the newswoman, “we’re going to see weather like we’ve never seen in Florida.”

“We should remind our viewers,” said the newswoman, “this wouldn’t be the first time it’s snowed in central Florida.”

“That’s correct,” the weatherman said. He reminded us of a couple inches that hit the state sometime in the early 80s. Then they cut to a field reporter at a local orange grove, interviewing a citrus farmer. The poor guy was talking about the fate of his crop. If the oranges froze, they would be ruined. He said he couldn’t afford to miss an entire season’s profit.

“This farm has been in my family for four generations,” he spoke into the camera.

My mother set plates down on the coffee table. “I thought we could eat in here since it’s just the two of us.”

“Ron won’t be joining us?”

She pretended like she didn’t hear me.

New Year’s breakfast was a tradition my father started when he and my mother first married. The idea was to kick the New Year off the right way, with food and family. Each of us was assigned a job. Nikki was the baker. She’d do one tray of something sweet, muffins or cinnamon rolls, and a tray of biscuits. My mother was on hash brown and bacon duty. My father did the peppers and eggs. I was his apprentice. According to him, every Italian man should know how to cook peppers and eggs.

“Nikki called earlier,” my mother said. “She’s going to eat breakfast with Jennifer’s family.”

I kept my eyes on the newscast. They had a chart up, showing the projected path of the storm.

“It’s getting cold,” my mother said. “Eggs are no good when they’re cold.”

“You know I have to move out,” I said. I heard her sniffle, but still refused to look at her. “This isn’t my home anymore.”

“Will you have breakfast with me, please?” she said. “It’s New Year’s.”

I got up off the easy chair and walked over to the couch. I took a seat next to her, close enough so we were touching. The mascara she put on the night before, her New Year’s Eve mascara, was running.

“We can’t eat New Year’s breakfast in front of the television like this,” I said. “Let’s bring these plates to the dining room.”

“Should I heat them up first?”

I took a look at the eggs. “This is no good.”

“I know your father usually does the eggs, but…”

“Let’s go into the kitchen. I’ll show you the correct way.”

We threw out the eggs my mother cooked, and I made some more, closely following my father’s recipe.

We sat in the dining room. We used the good china. We even lit the fancy candles. We talked like a mother and a son should talk. She asked about the classes I’d be taking the next semester. She gave me a small lecture on the dangers of drinking and driving. When she asked if I had kissed anyone at the stroke of midnight, my face went flush.

But mostly we talked about the weather. My mother remembered when it snowed back in the 80s. Her and my old man had been married less than a year.

“We didn’t get a lot of snow,” she told me. “Maybe a couple inches. But it came out of nowhere, froze the orange crops. Once they freeze, they’re no good to anyone. It’s not like you can just defrost them.”

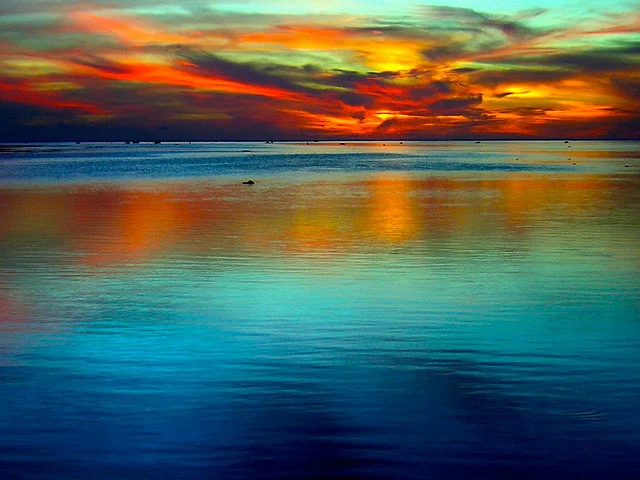

She told me people acted like it was the end of the world. But she thought it was beautiful, “like someone painted the city white.”

Hearing her talk about the snow like that, it got me thinking. Some people, they can see the beauty in something like a snowstorm. Others, they can only see the tragedy.

The storm never made it to us. It came close, but, at the last minute, a warm front from the Caribbean pushed it north. I was disappointed. After listening to my mother talk about the snow, about how beautiful it could be, I felt like I needed to see for myself.

Michael Cuglietta is a Florida writer. His work has appeared in or is slated to appear in The Gettysburg Review, Deep South Magazine, Saw Palm, The Hawaii Review, and Gertrude Press. While he does not have an MFA or English degree, he does have a license to sell health insurance, life insurance and variable annuities. He can be reached at cuges57@yahoo.com.