Writers on Writing #91: Anne Valente

Cicada, Snail Shell, Origin

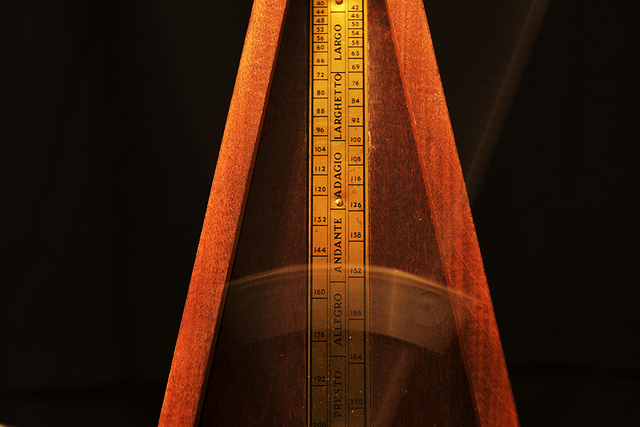

I grew up with a wooden metronome, a ticking steeple on my teacher’s upright piano. It kept time in her living room where our lessons were held every Monday for the ten years between my eighth birthday and my high school graduation. Each week my teacher adjusted the metronome’s pendulum to set the tempo of my practice. Debussy. Mendelssohn. Gershwin. Mozart. And the metronome’s ticking, an elemental sound lodged in my memory. I could see the passage of time happening: its shifting pendulum, the slow lilt of a metal weight. Rhythm as visceral, the weight’s swinging a match for my own growing heart.

In this way, I knew that someday I would die.

***

In The Art of Time in Fiction, Joan Silber writes, “The sequence of any fiction is, by its nature, the path of time evaporating.” We read from beginning to end. We write an opening and work our way through to a natural end.

Like sheet music, fiction carries its own time signature.

Silber notes too, however, that there is something called fabulous time in literature: that which defies linearity, the narrative that “can approach time by going round and round” where “repetition is a way of anchoring ornate narrative, of suggesting a grid of order within an overspill,” a form of narration often associated with magic realism and experimental fiction.

Long after I left my piano lessons I’d lay in the dark of my childhood bedroom and imagine not only notes scrawled across treble and bass clefs and my fingers finding them on a keyboard but an entire expanse of numbers, if music was determined by mathematics. Keys and time signatures, the product of integers. Integers that were infinite, I knew, from my math classes at school. I lay in bed and imagined the sky beyond the roof and its wide swath of Midwestern stars and considered infinity, an entire universe that just kept stretching and pushing beyond the bounds of my small brain. A terrifying endlessness, one that kept me awake wondering where the edge of the universe even was, an overspill of stars and the faint points of constellations.

But there was something in that terror: possibility. The possibility that time signatures aren’t everything, that we know the earth’s rhythms innately beyond gridding and mathematics. The possibility that nothing ends.

***

My parents work in hearing science, their research devoted to the mechanisms of the ear. Alongside the terms of my piano practice, the staccatos and codas and glissandos, I knew the word cochlea as a child. The ossicles of the ear: three small bones that swam in Lucite on my nightstand, a paperweight brought home from my parents’ offices. Incus. Malleus. Stapes. Words I whispered to feel their sound in my mouth. And cochlea, the locus of auditory signal that detects rhythm and pulse: the snail-shelled labyrinth of the inner ear. Proof that conch shells aren’t needed to hear ocean waves, that our bodies are built to understand the earth’s lull.

***

In a craft talk at the 2014 Sewanee Writers’ Conference, Jill McCorkle discussed finding sounds of origin in the process of writing fiction. Quoting Seamus Heaney:

Sing yourself to where the singing comes from.

In discovering voice in writing, discover your primordial sounds: the sounds that first shaped who you are.

As I lay awake in my childhood bed imagining infinity and its mind-bending possibilities the drone of cicadas pressed against my window, the whine of August pushing through thick clouds and summer steam toward autumn. And down the hallway, beyond my closed bedroom door: the hum of the television, my parents still awake.

The panes of my window a permeable border, the television and the trees.

***

In The Spell of the Sensuous, David Abram makes the case that language, having once developed in sync with the natural world, has distanced itself from the earth through the written word and through channels of communication that do not reciprocate with non-human forms of life. Computers. Televisions. Cell phones. Even books. He calls not for an end to the written word but for language that connects with the natural patterns of the earth, “the practice of spinning stories that have the rhythm and lilt of the local soundscape, tales for the tongue, tales that want to be told, again and again, sliding off the digital screen and slipping off the lettered page to inhabit these coastal forests, those desert canyons, those whispering grasslands and valleys and swamps.”

In Telling It Again and Again, Bruce Kawin makes a similar case for the origins of repetition in language, born not only of soundscapes but of the earth’s rhythms, of understanding ourselves within cycles that transcend linearity. He writes, “Primitive man learns from the periodic rebirth of the earth in spring that the pain of winter has no permanent effect, that the spring returns each year with its original vigor: that the destructive actions of time, in other words, are not permanent.” The cycles of the earth begin again and again, negating “the irreversibility of events – death, history, winter.”

Rhythm as landscape. Rhythm as beat, recurrence, wave. Rhythm as pulse. Rhythm as defiance, as destruction of linear time.

***

The television and the trees: two primordial sounds, at once human and not-human. My mode of communication the same as television, writing fiction a human-to-human pulse no different than the broadcast of 1980s television down the hallway.

But somewhere in the words, the featherweight of cicadas clinging to leaves.

***

My piano teacher and I worked through Beethoven, through Scott Joplin. We worked our way toward Bach’s fugues. Some of the most technically difficult pieces in piano notation, Bach’s numbered fugues are patterns of melody introduced and transfigured in variations across the composition. I learned how to introduce a melody with my right hand and repeat it again and again, at different paces and intervals, with my left. Permutations on theme, transposed across both hands on the keyboard: two voices played at once and at varying intervals, the same melody made new again. The metronome kept time atop the piano, a ticking weight to maintain my tempo. But the melody itself circled back, looping in rounds across the steady pace of the fugue.

Fugues exist in fiction as well. Kawin addresses the writer’s permutations on a theme in language wherein every “possible variation of a statement is given in the hope that one of the formulations may happen to correspond to the truth.” Rhythm as asymptote. Rhythm as movement. Rhythm as traveling forever toward truth, always unsayable. Kawin writes that “the drive to continue in this hopeless attempt at truth-saying is our only honorable activity within language. Its pain is our proper existential mode. So the attempt begins again, in another list, in another novel.” Rhythm as attempt: toward soundscape, toward speaking the earth’s unspeakability. Rhythm as permutation. Rhythm as fugue, a system of language circling back on its own mystery.

And rhythm as infinity: trying again, never reaching an end.

***

The rhythm of my writing process has lately been one of running my neighborhood streets. It is a dependable rhythm: Write. Run. Rinse. Repeat. There are other rhythms too: my shoes striking the pavement, the emergence of deer from the brush along my path, the return of goldfinches and bluebirds and hummingbirds in spring. How the days grow incrementally wider, the light long across the Midwestern summer. How the air thickens in August. How the sugar maples turn crimson in October. How the snow packs down beneath my sneakers in winter. And the necessary beat of my headphones across every season, a rhythm that keeps pace with my heartbeat.

Wu-Tang Clan. Eminem. Songs that form a new kind of metronome, a pulse, a beating back to primordial sound. Drives that insist upon themselves, that scream in every bass-lined beat we are alive, rhythms matched to nature’s soundscape. And this too: hip-hop, a modern form of the Bach fugue. Beats loop in permutation, loops that could continue forever if they wanted. Most rap songs simply fade rather than reaching a definitive end. Along the linear grid of a time signature and track, the beat loops back upon itself, a repeated melody whose end only comes when the artist fades the track.

A Tribe Called Quest. Dead Prez. Songs that match my fallible heart, a linearity beating toward an end, but also repeat again and again, contrapuntal and circling back, refuting the adamant march of time. Headphones and pavement. Cochlea. The wind through the trees, an indigo bunting alighting on a branch. A rhythm of drilled drumming and my own pulse, of light and fauna and blood.

***

Kawin writes of the body, “Most of us have been startled by our science teachers’ confident assertion that our cells are always dying and replacing themselves, so that every six or eight years we entirely change bodies. We are a new set of cells every time, begun from protoplasmic scratch, yet we maintain identity. Our existence is dependent not on that earlier set of cells, but on the present grouping. We are our own repetitions.”

As repetitions, we write in language: a system of logic. Our brains make sense of sensation by structure. Time signatures. Mathematics. Sentences, neatly formed. We speak the syllables of reason. We place a grid across the unsayable, everything in this world beyond speaking that we attempt to name. Love. Wonder. Joy. Our own deaths. We write anyway. The cycle of the earth, a rhythm that preceded our ability to speak it.

***

At six months old, my niece dances to the piped-in music of a grocery store. My sister takes her shopping and the store’s speakers blare merengue down upon the canned goods and fresh produce. My niece’s little body sways in the grocery cart seat. She awaits language. She awaits any concept of time. But she knows before anything else the rhythm and orchestration of music, how it matches the cadence of her own body’s cells. She knows something innate about sound long before she’ll learn that music carries a time signature, before language allows her words like beginning and end.

***

And time: plot’s linearity. That sentences have a beginning, a middle, an end.

There is something in the pairing of writing and running, in my insistence upon this symbiotic schedule. Psychologists point to the concept of flow, that those who write and those who run are susceptible to losing themselves to time. That writing and running require situating oneself beyond linearity, in a timeless frame of mind.

Earl Sweatshirt. Mobb Deep. Beastie Boys. Drake. The only beats keeping something other than time, something fixed to the soft pattering of rain or the shuffle of a box turtle across the pavement. A$AP Rocky. Lil Wayne. Mos Def. Jay-Z. Or else the whispering of leaves in the faint Midwestern winds, the television and the trees. A fugue both human and beyond human, needing only the ear to hear it.

***

And to capture the unsayable: do I need to say it?

I am afraid of the end.

I write against a time without maples or the fluttering of fall leaves to the pavement my shoes pound, of a lack of soft rustlings in the underbrush, of deer emerging from the fields. Of a lack of primordial sound, my hands to the piano. My niece swaying to song. My family all inside, the soft hum of cicadas to the window.

Rhythm as recurrence, immortality. Rhythm as revolt.

***

I write my way back to an earth that knows itself beyond time signatures and authorial gridding, a land that abides by its own signature and the possibility that nothing moves in straight lines. A land of cycles. Of pulse. My own Midwestern heart. Rhythms of recurrence and return, of cadence beyond clock. What of these cicadas that know when to whine, when to crawl up from the cave of the earth? What of dog day cicadas, those that unearth themselves every August, or else those that push up from Missouri soil every fifteen or seventeen years and drone on for a stretch of weeks before dying back to their periodical return, a clock beyond time that they feel and I’ll never know? What of ruby-throated hummingbirds, the only kind that grace the Midwest, how they know when and how to cross the Gulf of Mexico every spring in a single, wing-beaten burst? What of the pulse of strong winds that whistle through a hickory’s leaves and how they sometimes form funnels that spiral down from the sky? What of autumn, the last of the leaves, how red-breasted robins know when to go?

***

I am so many bodies apart from a small child awake in a bedroom, from the pulse of a wooden metronome and the lilt of cicadas beyond a window. But sometimes I leave the television on in the other room as I write sentences that circle back on themselves, a quiet hum behind a closed door. Sometimes I am still safe in my bed, the ceiling nothing more than a roof that keeps from view an infinite span of stars, my parents forever in the living room down the hall as I sleep.

Anne Valente's first short story collection, By Light We Knew Our Names, releases from Dzanc Books in October 2014. She is also the author of the fiction chapbook, An Elegy for Mathematics. Her fiction appears or is forthcoming in One Story, Ninth Letter, Hayden's Ferry Review and The Normal School, among others, and her essays appear in The Believer and The Washington Post.